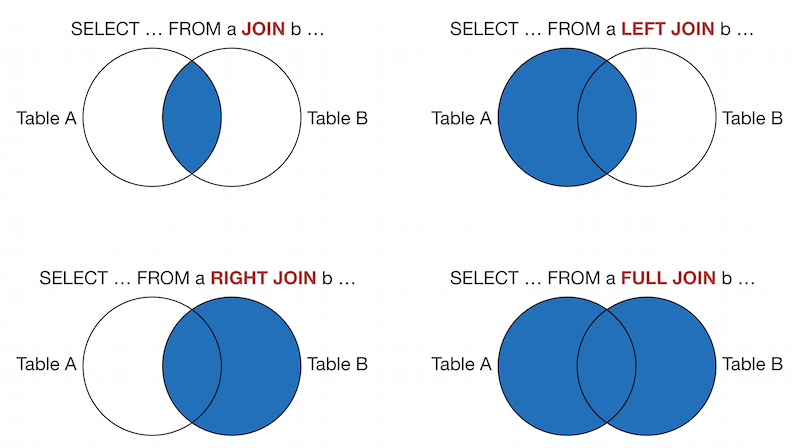

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Aggregation and JOINs ## Computational Statistics<br>& Operations Research ### <a href='htps://janusvm.github.io'>Janus Valberg-Madsen</a> ### 2019-03-25 @ Aalborg University --- # Recap of last time - Introduction to relational databases - Basic syntax - How to use psql and pgAdmin --- # Today's topics - Summarising data - Using data from multiple tables with `JOIN` - How to construct and use _subqueries_ ??? Today we will dive into SQL queries involving data from multiple sources and how to get just the information you need from the database. - We'll look at how to produce different kinds of summaries, both on whole tables and on a by-group basis - More complex queries involving selecting from tables multiple times - Joining tables together to match related tuples from different sources - Dealing with missing values --- layout: false class: snowstorm, middle, center # Summarising data computing a single result from a set of input values ??? To summarise data means to calculate aggregate results from many rows into few or a single row. --- ## What is a summary? ```sql SELECT summary_function(expr) [AS new_name] [, ... ] FROM table [ GROUP BY grouping_variables ] ``` .pull-left[ A _summary function_ aggregates a set of values into one single value (summary)  ] .pull-right[ Use the `GROUP BY` clause to create summaries on a by-group basis  ] .footnote[ (image source: [Data Wrangling cheat sheet by RStudio](https://www.rstudio.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/data-wrangling-cheatsheet.pdf)) ] ??? More often than not, you don't want to pull out data as-is from your database, but rather calculate some summaries exposing some insight. The basic syntax for that is as shown: in the column list of `SELECT`, you make calls to so-called _summary functions_, optionally grouping the input values by one or more variables. --- ## Summary functions .pull-left[ - `count(*)`: the number of input rows - `count(expr)`: the number of rows where `expr` is not null - `avg(expr)`: the average of the input values - `sum(expr)`: the sum of the input values - `max(expr)`: the maximum input value - `min(expr)`: the minimum input value ] .pull-right[ - `bool_and(expr)`: true if all input values are true - `bool_or(expr)`: true if at least one input value is true - `corr(Y, X)`: correlation coefficient between X and Y - `stddev(expr)`: standard deviation of input values - `variance(expr)`: variance of input values ] .footnote[ Many more are available, see the [documentation](https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/functions-aggregate.html) ] ??? Here is a quick overview of some of the summary functions that you'll likely need to use. Many more are available. --- ## Filtering on summaries: the HAVING clause - `WHERE`: filter using a condition on individual rows, before grouping - `HAVING`: filter using a condition on aggregations, after grouping ??? When you work with grouped data, you may wish to filter on either individual rows or groups. The `WHERE` clause, which you saw last time, does the former, and the `HAVING` clause does the latter. -- ```sql SELECT carrier, count(*) FROM flights WHERE origin = 'JFK' GROUP BY carrier HAVING min(distance) > 1000; ``` The carriers whose flights from JFK airport all fly at least 1000 miles to reach their destinations, and their respective number of flights ??? Here is a small example of the usage of `HAVING`. -- Syntax rule of thumb: - `WHERE` goes _before_ `GROUP BY` (filter before grouping) - `HAVING` goes _after_ `GROUP BY` (filter after grouping) --- layout: false class: snowstorm, middle, center # Combining data from different tables how to use the JOIN clause --- ## What is a join? .pull-left[ `JOIN`: clause for combining relations. .footnote[.pull-left[ In the examples in this section of the slides (which I've borrowed from [r4ds.had.co.nz](https://r4ds.had.co.nz)), the tables used are: - `x`, with columns: `key` and `val_x` - `y`, with columns: `key` and `val_y` ]] ] .pull-right[ ```sql x JOIN_TYPE y [ JOIN_CONDITION ] ```  .center[⬇️]  ] ??? An SQL `JOIN` clause is an instruction to combine columns from several tables in a database. The code snippet should be read as: "Join `x` and `y` together with `JOIN_TYPE` optionally conditioning on `JOIN_CONDITION`" On the following slides, we'll look at the concrete `JOIN_TYPE` and `JOIN_CONDITION` you can use. The figures for the different types of joins will use dots and lines to denote the data that will be returned. --- ## Cross join `x CROSS JOIN y` ➡️ cartesian product of the rows in `x` and `y` ```sql SELECT * FROM x CROSS JOIN y; SELECT * FROM x, y; ``` If - `x` has dimensions `\(n_x \times m_x\)`, and - `y` has dimensions `\(n_y \times m_y\)`, then their cross product has dimensions `\(n_x n_y \times (m_x + m_y)\)` ??? The official PostgreSQL documentation groups the types of joins into two: - cross join - qualified join The `CROSS JOIN` between `x` and `y` is simply the table you get by taking all columns of both and return all possible combinations of rows --- ## Qualified joins ```sql SELECT * FROM x { [INNER] | { LEFT | RIGHT | FULL } [OUTER] } JOIN y ON boolean_expression; SELECT * FROM x { [INNER] | { LEFT | RIGHT | FULL } [OUTER] } JOIN y USING ( join column list ); SELECT * FROM x NATURAL { [INNER] | { LEFT | RIGHT | FULL } [OUTER] } JOIN y; ``` ??? In contrast to the cross join, the _qualified joins_ only return rows from the two tables which are considering to be "matching", given some condition that evaluates to a boolean value. The code snippet shown is from the documentation, and it should be read like this: - For elements in braces `{ ... | ... }`, exactly one of the candidates (delimited by a `|`) must be present - Elements in brackets `[ ... ]` are optional - Each row in the snippet corresponds to a different way of specifying the join condition --- ## Qualified joins: INNER JOIN ```sql SELECT * FROM x JOIN y ON x.key = y.key; SELECT * FROM x INNER JOIN y USING (key); SELECT * FROM x NATURAL JOIN y; ``` .pull-left[  ] .pull-right[  ] ??? An `INNER JOIN` is the join that selects records found in both `x` and `y`. That means, that for each row of `x`, the joined table has a row for each row in `y` that satisfies the join condition with that `x`-row. For example: - on the left, both `x` and `y` has keys `1` and `2`, so the resulting inner join contains a row for each of these two keys with all the remaining columns from the respective tables - on the right, `x` has duplicate keys, so the matching rows from `y` are duplicated (if both tables have multiple keys, you get the cross product of the matching rows) **[covering the example snippets]** - `INNER JOIN` is the default join type that PostgreSQL uses, if you just type `JOIN`; the keyword `ON` lets you match columns with qualified names (i.e. `table.colum`) - the keyword `USING` can be used when the columns being matched have the same name in the two tables - The `NATURAL` keyword is shorthand for `USING` all the common column names; if there are no common column names, it produces a cross join --- ## Qualified joins: OUTER JOIN .left-balanced[  ] .right-balanced[ ```sql -- left outer joins SELECT * FROM x LEFT JOIN y ON x.key = y.key; SELECT * FROM x LEFT OUTER JOIN y USING (key); SELECT * FROM x NATURAL LEFT JOIN y; ``` <br/> ```sql -- right outer joins SELECT * FROM x RIGHT JOIN y ON x.key = y.key; SELECT * FROM x RIGHT OUTER JOIN y USING (key); SELECT * FROM x NATURAL RIGHT JOIN y; ``` <br/> ```sql -- full outer joins SELECT * FROM x FULL JOIN y ON x.key = y.key; SELECT * FROM x FULL OUTER JOIN y USING (key); SELECT * FROM x NATURAL FULL JOIN y; ``` ] ??? An `OUTER JOIN` takes all the rows for one or both of the source tables, depending on type, and adds missing values where the join condition was not met. The `OUTER` keyword is completely optional, as it is already implied by the keywords `LEFT`, `RIGHT`, and `FULL`. - `LEFT JOIN`: all the rows of `x`, with the columns of `y` padded with `NULL` for non-matching keys - `RIGHT JOIN`: same as left join, expect with the roles of `x` and `y` reversed - `FULL JOIN`: all rows of both tables, with the columns of both padded with `NULL` whenever they have non-matching keys, respectively --- ## Qualified joins: alternative visual representation  .footnote[(image source: [cmascenter.org](https://www.cmascenter.org/cost/sql_basics.html))] ??? Oftentimes in literature, you see the different types of joins represented as Venn diagrams, alluding to mathematical sets. Think of these sets as sets of keys; different tables often have different colums, so the set interpretation doesn't make a lot of sense when considering whole rows --- layout: true ## Useful joins without dedicated syntax ??? The semi join and the anti join do not have their own syntax in PostgreSQL. Instead, the query planner may or may not use these joins for optimisation purposes (we will see an example of that in Lecture 04). However, in R (`dplyr`), they _do_ have syntax, which we shall see in Lecture 03. In _R for Data Science_, Hadley Wickham calls these types of joins _filtering joins_. ## Semi join The semi join selects all rows from `x` that have a matching key in `y`, but without adding any data from `y`. This can be achieved in PostgreSQL using a nested query, in which you simply identify the rows in `y` that have matching keys. Notice the `SELECT 1 FROM y` line; the actual data selected from `y` doesn't matter, as it isn't used anyway, so you can select anything you want here (including `*`). ## Anti join The anti join is the opposite of the semi join. It selects all rows from `x` that do _not_ have a matching key in `y`. --- .pull-left[ ```sql -- semi join SELECT * FROM x WHERE EXISTS ( SELECT 1 FROM y WHERE x.key = y.key ); ```  ] .pull-right[ ```sql -- anti join SELECT * FROM x WHERE NOT EXISTS ( SELECT 1 FROM y WHERE x.key = y.key ) ```  ] --- count: false .pull-left[ ```sql -- semi join SELECT * FROM x WHERE EXISTS ( * SELECT 1 FROM y * WHERE x.key = y.key ); ```  ] .pull-right[ ```sql -- anti join SELECT * FROM x WHERE NOT EXISTS ( * SELECT 1 FROM y * WHERE x.key = y.key ) ```  ] ??? ## Subquery? This inner query is an example of what's called a _subquery_. **[next slide]** --- layout: false name: subqueries class: snowstorm, middle, center # Subqueries queries nested inside another query, enclosed in parentheses ??? A subquery is also called an _inner query_ or _inner select_. Such an expression can be in many different cases: - after a `FROM` clause in place of a table - after a binary operator, if the subquery returns only one value - after an array comparison function, if the subquery returns only one column The last case is one you'll see often, so let's explore that a bit --- layout: true ## Subquery expressions --- .left-column[ ### EXISTS ] .right-column[ ```sql SELECT * FROM flights WHERE EXISTS (SELECT 1 FROM planes WHERE tailnum = flights.tailnum); ``` Selects the flights where the plane's tail number is recorded in the `planes` table. ```sql SELECT * FROM flights WHERE NOT EXISTS (SELECT 1 FROM planes WHERE tailnum = flights.tailnum); ``` Selects the flights that do _not_ have a corresponding entry in the `planes` table ] ??? An `EXISTS` expression can be used to make semi and anti joins, as demonstrated on the previous slide. Here is an example using the `nycflights13` data. --- name: subquery-in .left-column[ ### EXISTS ### IN ] .right-column[ ```sql SELECT * FROM flights WHERE tailnum IN (SELECT tailnum FROM planes WHERE manufacturer = 'EMBRAER'); ``` All the flights flown by a plane manufactured by EMBRAER ```sql SELECT * FROM flights WHERE tailnum NOT IN (SELECT tailnum FROM planes WHERE seats < 50); ``` All the flights flown by larger planes (i.e. 50 or more seats) ] ??? An `IN` expression can for example be used to make a filtering join, where you condition on additionally filtered data from another table. There is actually a subtle error on the slide; can you identify it? ➡️ the last sentence; in addition to all flights flown by larger planes, the second query will also return the ~50,000 flights flown by planes that don't have a corresponding entry in the `planes` table --- .left-column[ ### EXISTS ### IN ### ANY/SOME ] .right-column[ ```sql SELECT * FROM airports WHERE alt >= ANY (SELECT MAX(alt) FROM airports GROUP BY tzone); ``` The airports that have an altitude higher or equal to the maximum altitude of any time zone. The keyword `SOME` is an alias for `ANY`. ] --- .left-column[ ### EXISTS ### IN ### ANY/SOME ### ALL ] .right-column[ ```sql SELECT * FROM airports WHERE alt >= ALL (SELECT AVG(alt) FROM airports GROUP BY tzone); ``` The airports that have an altitude higher or equal to _all_ the average altitudes by time zone. ] --- layout: true ## WITH queries The `WITH` clause is used to build _common table expressions_ (CTE), which can be thought of as temporary tables that exists for just one query. ??? If you have a query with a lot of subqueries, it might be beneficial for organisational purposes to use CTEs, especially if you end up using a subquery multiple times. Here is a (contrived) example to illustrate it; --- --- ```sql WITH agg_tbl1 AS (SELECT AVG(dep_delay) AS avg_dep_delay, AVG(air_time) AS avg_air_time FROM flights GROUP BY origin ), ``` ??? - The `WITH` clause goes before the `SELECT`; here, we define a temporary table called `agg_tbl1`, calculating the average `dep_delay` and `air_time` by `origin`. We can define as many of these as we like, separated by commas. --- ```sql WITH agg_tbl1 AS (SELECT AVG(dep_delay) AS avg_dep_delay, AVG(air_time) AS avg_air_time FROM flights GROUP BY origin ), agg_tbl2 AS (SELECT MIN(avg_dep_delay) AS min_avg_dep_delay, MIN(avg_air_time) AS min_avg_air_time FROM agg_tbl1 ) ``` ??? - The `WITH` clause goes before the `SELECT`; here, we define a temporary table called `agg_tbl1`, calculating the average `dep_delay` and `air_time` by `origin`. We can define as many of these as we like, separated by commas. - After the comma, we define `agg_tbl2`, where we calculate the minimums of the quantities just calculated in `agg_tbl1`. --- ```sql WITH agg_tbl1 AS (SELECT AVG(dep_delay) AS avg_dep_delay, AVG(air_time) AS avg_air_time FROM flights GROUP BY origin ), agg_tbl2 AS (SELECT MIN(avg_dep_delay) AS min_avg_dep_delay, MIN(avg_air_time) AS min_avg_air_time FROM agg_tbl1 ) SELECT * FROM flights WHERE dep_delay < (SELECT min_avg_dep_delay FROM agg_tbl2) AND air_time < (SELECT min_avg_air_time FROM agg_tbl2); ``` The flights where both the delay on departure and air time are below all the averages by origin. ??? - The `WITH` clause goes before the `SELECT`; here, we define a temporary table called `agg_tbl1`, calculating the average `dep_delay` and `air_time` by `origin`. We can define as many of these as we like, separated by commas. - After the comma, we define `agg_tbl2`, where we calculate the minimums of the quantities just calculated in `agg_tbl1`. - Finally, the actual `SELECT` expression that brings it all together. So what was the purpose of it? Instead of having two subqueries, where we group by and summarise the `flights` data, we instead do it once and reference it twice, using a CTE. --- layout: false # A word on NULLs `NULL` is a special marker that indicates a value does not exist in the database. ??? The concept of nulls in SQL is similar to that of `NA` in R. It is a marker of missingness, not a value in itself. -- To test if a value is null: - ❌ `value = NULL` (returns `NULL`) - ✅ `value IS NULL` (similar to `is.na` in R) ??? Since it is a special marker, you need special syntax to test for nulls. -- ```sql -- XOR join SELECT * FROM x FULL JOIN y USING (key) WHERE x.key IS NULL OR y.key IS NULL; ``` ??? An example where it can be used: an "XOR" join, i.e. the rows in `x` or `y`, where they don't have keys in common. -- To control where nulls are placed when ordering a column: - `ORDER BY col NULLS FIRST` - `ORDER BY col NULLS LAST` --- layout: false name: exercises # Exercises .pull-left[ Today's [sqlzoo.net](https://sqlzoo.net) exercises are: - [4 SELECT within SELECT](https://sqlzoo.net/wiki/SELECT_within_SELECT_Tutorial) ([+quiz](https://sqlzoo.net/wiki/Nested_SELECT_Quiz)) - [5 SUM and COUNT](https://sqlzoo.net/wiki/SUM_and_COUNT) ([+quiz](https://sqlzoo.net/wiki/SUM_and_COUNT_Quiz)) - [6 JOIN](https://sqlzoo.net/wiki/The_JOIN_operation) ([+quiz](https://sqlzoo.net/wiki/JOIN_Quiz)) - [8 Using NULL](https://sqlzoo.net/wiki/Using_Null) ([+quiz](https://sqlzoo.net/wiki/Using_Null_Quiz)) ] .pull-right[ Additional exercises for the fast learners: 1. Fix the error on [this slide](#subquery-in) That is, show the flights with planes that _are known_ to have 50 or more seats 2. Show flights with planes that have flown at least 100 flights 3. What does it mean for a flight to have a missing `tailnum`? What do the tail numbers that don't have a matching record in `planes` have in common? (hint: one variable explains ~91% of the problems) ] ??? Hint for extra exercise 3: check `?nycflights13::planes` --- layout: false name: links class: polarnight # Links 🔗 - Course home page: <https://janusvm.github.com/aau-csor-db> - These slides: <https://janusvm.github.com/aau-csor-db/slides/02-aggregation> - Relevant pages from the PostgreSQL docs: - Aggregate functions: <https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/functions-aggregate.html> - Table expressions: <https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/queries-table-expressions.html> - `WITH` queries: <https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/queries-with.html> - Functions reference (SQLzoo): <https://sqlzoo.net/wiki/Functions_Reference> - R For Data Science: <https://r4ds.had.co.nz> - Section _Relational data_: <https://r4ds.had.co.nz/relational-data.html>